|

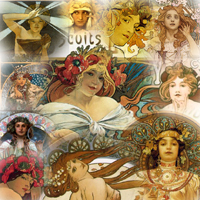

It is said that Art Nouveau is among the last remarkable styles of art which have ever appeared in history. In fact, Art Nouveau forms the end of a long line of art styles like Romance, Renaissance, Baroque and others. Art Nouveau sharply boomed at the end of the 19th century and this boom lasted approximately for only one decade. After that, Art Nouveau was transformed into a more advanced and fresh style of art. In the 1890s, many young artists were not satisfied with the fact that industrialization was spread all over western Europe. “Art Nouveau attempted to achieve coexistence between functional surroundings and the intimacy of private life” (Duane, 1996, p. 6). Art Nouveau was exactly what artists demanded (Duane, 1996). “It was characterised by a renewed interest in natural, flowing forms and a subjective feeling for spiritual content. Curves, spirals and rich ornamentation became popular features of the style and were applied to glass, ceramics, architecture and graphic art” (Duane, 1996, p. 6). Art Nouveau stood very close to Symbolism and took ideas from French Rococo and Japanese art (Ellridge, 1992). A new style became immediately very popular and spread quickly in the main cultural centres of western Europe, especially in Paris, Vienna, Munich and Berlin, as well as in Great Britain and the USA. The most famous Czech artist of the Art Nouveau era is definitely Alphonse Mucha (Alfons Mucha), who became well known especially thanks to his posters for Sarah Bernhardt’s theatre in Paris. It is necessary to add that Mucha didn’t paint only posters. In addition to posters, he created many book illustrations, ornamental panels, advertisements, jewellery, decorative little statues, architectural designs, and a way to make manufactured goods more interesting, e.g. reproductions of his paintings and drawings appeared on biscuit boxes, postage stamps, and banknotes (Moucha & Řapek, 2000). This paper will discuss in brief the artist’s early life and work, the period of his greatest fame, his return to Czechoslovakia, and his contribution to art. It is reasonable to start with the early life and work of Mucha. Alphonse Maria Mucha was born in Ivančice, a Moravian town, in 1860. Alphonse had two sisters: Anna and Anděla. His father Ondřej worked as an usher in the local district court and Ondřej’s second wife Amalia was a daughter of a rich miller (Kusák & Kadlečíková, 2000). Already as a boy, Alphonse liked to draw pictures and sketch other people’s faces; he was also talented in singing. Thanks to his unusual voice, he got a choral scholarship at St Peter’s Church in Brno (Duane, 1996). Young Alphonse studied there at the Slavic gymnasium. Afterwards, Mucha wanted to study at the Art Academy in Prague, but he was not accepted there. Instead of studying, he started to work as a clerk at the local district court in his hometown. Two years later, he changed his job and left to make up theatre scenery for a Viennese company. But unfortunately, after some time he was dismissed and he had to find a new job. During his next jobs he met the important person who recognised his talent and helped him to get into the Art Academy in Munich. After two years he moved to Paris to go on in his studies (Kusák & Kadlečíková, 2000). But this smooth life did not last for long. In 1889, Mucha had to leave the Academy and start earning money for his living. Fortunately, there were a lot of job opportunities in Paris for such a skilled artisan like Mucha. First of all, Mucha illustrated schoolbooks and popular novels for a Parisian publishing house; his next opportunity to show his talent was a realisation of the 1884 calendar for a manufacturer of well-known inks (Ellridge, 1992). All those jobs were good for Mucha at that time, but the most challenging task had yet to come. One day, Alphonse Mucha got an opportunity to create a poster for a theatre of Sarah Bernhardt and this poster actually started the period of Mucha’s greatest fame. The poster had to be designed for a play of Gismonda, in which Bernhardt performed as a main character (Ellridge, 1992). At that time, Bernhardt already was a very famous actress who was not only a beautiful woman, but also a dedicated and charming person (Duane, 1996). She liked Mucha’s work and offered him a contract for the next six years (Ellridge, 1992). Mucha painted many other posters for her (Duane, 1996) and became famous practically overnight (Ellridge, 1992). The poster of Gismonda was admired by most Parisian people because of the fact that it was something new in art. Not long after Mucha’s poster first appeared in the public, Art Nouveau started to be often called Le Style Mucha (Duane, 1996). The artist’s work became quickly a part of everyday life; posters, decorative panels, biscuit boxes, chocolate bars and perfumes or liqueur bottles with labels designed by Mucha were sold everywhere (Ellridge, 1992). By 1903, the painting of similar motifs all the time started to tire Mucha; the motif of his paintings usually was a woman with flowers in a romantic setting. In fact, devotion to the Slav people gave him the idea for a project which he named The Slav Epic: monumental paintings illustrating the history of the Slavs which he wanted to give to the Czech people as a present (Duane, 1996). One year after, Mucha arrived in America, where he wanted to raise money for The Slav Epic by painting portraits. Unfortunately, he painted portraits of rich women slowly and had to accept orders for magazine covers, posters and advertisements. Mucha’s dream remained unfulfilled till he met Charles R. Crane, an American industrialist and diplomat, who promised him to fund the whole project (Kusák & Kadlečíková, 2000). Now, Mucha was a little bit closer to his dream and it was the right time to return to his beloved homeland. In 1909, Mucha returned to Czechoslovakia and started to make preparations for his project of The Slav Epic. First of all, it was necessary to find an appropriate studio. One year after, Mucha visited his friends in Castle Zbiroh in Bohemia and found there space which was suitable enough to place several canvases of such enormous size side-by-side and work on them simultaneously. Mucha studied Slavic culture carefully for a long time and asked different scholars, sociologists, historians and experts on Slavic culture for essential details. He even went to Russia, Poland, Serbia and Bulgaria to get to know people’s customs and make some important sketches for further painting (Ellridge, 1992). Some other jobs for Mucha appeared from time to time. Mucha wanted to be useful to his nation and, therefore, as soon as a new building for the Municipal House (Obecní dům) was built in Prague in the Art Nouveau style, Mucha offered to decorate the interiors without charge as a present to the Czech people. His other task was to make sketches for postal stamps. Mucha completed their design in a very short time. Later, when he designed banknotes, he even used a portrait of his own daughter for the reverse side of them. In St Vitus’s Cathedral people often admire a beautiful stained-glass window that was also made by Mucha (Ellridge, 1992). At that time, Mucha worked on many different projects, but always with the same virtuosity which was unique to him. Alphonse Mucha was really dedicated to the idea of The Slav Epic and that is why he painted so fast. By December 1912, the first three six-by-eight-metre paintings were done. In 1919, after World War I, Mucha exhibited the first eleven canvases in the Carolinum Hall in Prague and many people admired these paintings. The next two exhibitions took place in America and both of them were very successful, too. Mucha worked on The Slav Epic until the beginning of the World War II, when his project was interrupted by the German invasion of Czechoslovakia and not long after he had been questioned by Nazi troops (Duane, 1996). Unfortunately, Alphonse Mucha died on 14th July 1939 shortly before his 79th birthday (Kusák & Kadlečíková, 2000). His wife Marie, daughter Jaroslava, and son Jiří were left alone after Mucha’s death, and The Slav Epic remained uncompleted. The work of Alphonse Mucha is very popular everywhere, but it may seem that it is more popular abroad than in his homeland. The most controversial work is The Slav Epic, which was admired by the public and criticised by the critics who described the paintings as ‘empty historic bombast’ (Duane, 1996). The critics argued that The Slav Epic was a romantic idea which should have been realised much earlier because at the beginning of the 20th century it was relatively out-of-day (Ellridge, 1992). However, Alphonse Mucha influenced the world of art and fashion, especially during his stay in Paris between 1894 and 1904, when he was developing ideas of Art Nouveau often called Le Style Mucha. Mucha’s career was sixty years long and he created a unique art collection ranging from posters to decorative panels, from sculpture to historical canvases (Duane, 1996). There is no question that Alphonse Mucha was the leading artist of the Art Nouveau style. Mucha’s work is still, after one century, very popular all over the world. His fame was brought back several decades after his “Parisian” period and now everyone can see all that beauty in the collections of art museums and galleries all over the world. Mucha even became the favourite artist of Japanese art lovers who decided to open a museum of Alphonse Mucha (Kusák & Kadlečíková, 2000). There is a lovely Mucha Museum in Prague, too.

To sum up, this paper gave brief information about Art Nouveau, Mucha’s early life and work, the period of his greatest fame, his return to Czechoslovakia, and his contribution to art. It is interesting, that Alphonse Mucha was very popular during his life and remains popular after so many years. This shows that Mucha’s artistic efforts had lasting value, and his work is still living thanks to his admirers.

|